Question: why would you replace a highly paid actor with a computer-generated double?

Answer: because you could. *wink wink*

Kidding aside, there are many reasons film producers and directors choose to recreate a full human (sometimes less than human, other times more than human; more on this later) using 3D for a scene or even a whole film. These reasons can range from budget constraints to time crunches to actor schedules or contract issues (not a joke) to safety concerns to the impossibility of achieving the director’s vision via practical effects and live-action shots.

And the results achieved with digidoubles are as varied as the reasons behind using them. When done right, digidoubles are indistinguishable from real actors, and scenes employing CGI models flow seamlessly with scenes with real live footage. When done wrong, the results can be horrific, laughable, or uncanny (quick digression here: “uncanny valley” is a term that is used in cinematic and VFX circles to refer to a digidouble that may seem human but elicits an eerie feeling from viewers due to its artificialness and failure to fully capture human expressions. Think deep fakes).

Now, bad digidoubles are a result usually of two things: time crunch or budget constraints. These two issues are where render farms can help out production. Render farms, by virtue of having hundreds of powerful machines all dedicated to rendering frames for various projects, are leaps and bounds faster than rendering locally on any one machine. Scenes that would take hours or days to render on your computer can be completed in minutes or hours. It’s sheer hardware power. At GarageFarm, you get to choose which kind of CPUs or GPUs you’d like to handle your project (check it out here).

As for the budget side: sure, almost every render farm service charges a fee. But rendering using your own computer shouldn’t be seen as “free” since doing that ties up your CPU; meaning, you can’t do anything else. And every hour your computer sits there rendering is an hour you are not able to work on other scenes or projects. And what happens when after waiting for hours on end for your project to render on your computer it turns out there’s an error somewhere? All those hours will have just been for nothing. At our cloud render farm, the fee also goes to having a 24/7 support team that is on standby should there be any issues regarding your project.

(Curious how fast and how much your project can be rendered with GarageFarm? Test out scenarios with our cost calculator.)

Now that we know what digidoubles are, let’s take a look at some examples.

Gollum. Peter Jackson’s technical prowess combined with Andy Serkis’ superb acting brought to life Gollum, one of the most memorable CGI characters of all time. You might argue that Gollum isn’t technically a digidouble because the CGI version doesn’t substitute for a real actor. But I dare you to find a 3-foot 6-inch human with pear-sized eyes and feet of a 7-footer who can deliver the same powerful dramatic performance as Andy Serkis. In fact, this even makes the technical achievement of Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy even more miraculous. I daresay Gollum can even out-act some real-life actors right now. Now, behind the lonesome Gollum are hundreds and hundreds of computers set up by Weta Digital in its own rendering farm in order to bring to life this one-of-a-kind creature on the big screen.

Davy Jones. This villain from The Pirates of the Caribbean franchise is considered by many as the best digital character (again, not strictly a digidouble; more of a digibeing) of all time. The filmmakers took absolute pains in designing and crafting the look of this menacing squid-man. Perhaps the secret sauce in designing this digital villain lies in the decision to integrate the actor Bill Nighy’s actual eyes for the character in the final output and not compose the eyes in CG.

Another genius move by the creators was to turn the weakness of the medium into an advantage: back in the day, 3D renders tended to have a sheen or gloss to them that made human or animal skin unrealistic. But since Davy Jones is a squid-man and is always glistening with wetness, the sheen worked for the character’s look. Davy Jones was crafted by the prestigious CG company Industrial Light and Magic (ILM). ILM has its own dedicated render farm, the specs of which sound hyperbolic to people outside of the industry: 7,000 processors outputting a total of 1 petabyte of data every 24 hours. The machines run so hot that ILM needed to install an air conditioning system fit for a jet engine.

The Na’vi in Avatar. James Cameron is a master world-builder and that includes his excellence in bringing non-human species to life. The Na’vi are human-like in their form and expressions but they are 9 to 10 feet tall and their skin is blue. Similar to Gollum, the production used motion capture extensively to give expression and movement to the Na’vi. Cameron and his team figured all that out and more to bring forth breathtakingly detailed and convincingly realistic digidoubles digibeings. Like Gollum, the Na’vi and the rest of the world of Avatar were rendered by Weta Digital and its own render farm built on a 10,000 square foot property in New Zealand.

Marvel’s superheroes and villains. From Hulk to Ant Man, Iron Man to Thanos, Spidey to Captain Marvel, the films in the Marvel cinematic universe are replete with convincing, cool, and badass digidoubles. Rendering a full human body into CG is par for the course for Marvel’s CG artists: all of Spider-Man’s scenes in Civil War are all digidouble’d because Tom Holland joined the cast late (one month into the shoot) and 3D was the most efficient way to bring him in as Spidey. Besides, it’s easier for production to render his spider suit in CG than craft it in real life (it’s made of fabric with metallic inlays and whatnot). Plus, it’d be suffocatingly hot for Tom Holland to act with his mask on for hours on end.

Marvel’s artists also do partial digidoubling on actors, like how they rendered Tony Stark in 3D from the neck down when he has his helmet off, or Steve Rogers’ feet in a scene where he was running barefoot, or the suit the Avengers wore when they jumped into the time machine (production team couldn’t finalize the design in time for the live shoots so they CG’d in the final design instead). With these movies all produced under Disney, safe to say that ILM has had its hand on creating these digidoubles. This means that the artists who worked on these digidoubles have had access to the enormous power of ILM’s own render farm.

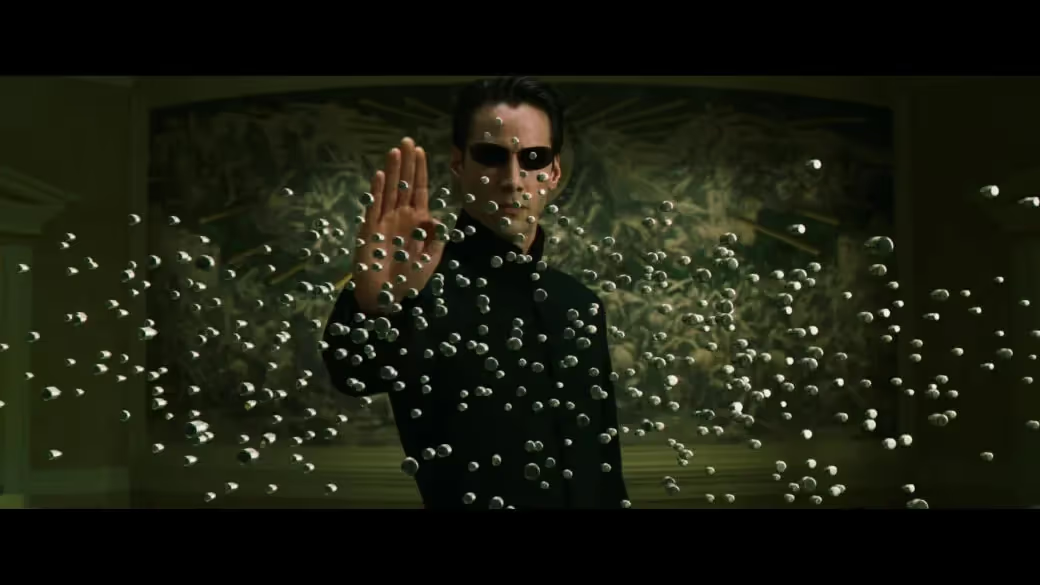

Neo in Matrix Reloaded. The first Matrix film introduced visual effects and filming techniques that are in some way still being used to this day. It was that revolutionary and cool. In the second film of its trilogy however, there is a sequence where Neo fights an endless stream of Agent Smiths that looks like a cut scene from a PS2 game. Neo looked doughy, his skin seemed inhuman, and his signature black coat looked glued to his body and seemed made of rubber. It was bad.

Renesmee. The baby revealed at the end Twilight: Breaking Dawn is the living, breathing definition of Uncanny Valley. The infant’s face looked human enough but…there was something eerie and disturbing about it. For one, you could tell that the face was superimposed to the live action scene; something about the lighting made the baby’s face look detached from everything else. Perhaps the idea itself behind the character was odd in itself – being half-vampire, the creators wanted a baby that was outwardly infantile but inwardly mature, since her vampire powers make her advance and grow rapidly (Renesmee was able to talk just 7 days after being born). At any rate, no one seemed delighted to see this baby, audience and cast alike.

Scorpion King in The Mummy Returns. I like Dwayne Johnson and he always looks cool and awesome wherever you see him but…not in this film. They tried to pull off a half-human, half-scorpion monster villain but it looked like they ran out of time for his scenes. The Scorpion King looked doughy, lacked detail, and had an unfinished look to it. The Scorpion King render was so poorly lit that it looked out of place in the environment. The Scorpion King visuals had no, um, sting.

We can’t possibly detail here all the ways you can create a digidouble the same way we can’t possibly list down here all the digidouble there ever were. Allow me however to outline for you one way to create a digital version of a human for cinematic purposes if you don’t have the budget, manpower, and timeline of a Hollywood studio.

Step 1, photogrammetry. This is the step where you take reference photos of the person you want to create a digidouble for then feeding these photos into a software that creates a mesh from those photos. One such software is Meshroom. The output from this phase, your mesh, will be your reference for the next step.

Step 2, modeling the head. Software like the Blender addon Human Generator or MakeHuman or MetaHuman give you human presets that you can refine further. This saves us from sculpting our digidouble from scratch which, I don’t need to tell you, is a laborious and time-consuming process.

So you take your mesh reference and a full body reference photo, open these up in the software, then line up a close-enough human preset to your reference mesh and photo. From here, it’s now a matter of continuous pushing and pulling on the 3D model and adjustments on the sliders to now get the preset to look like the person you’re trying to model. Here you’re matching the length and curve of the nose bridge, the depth of the eye sockets, the protrusion of the cheekbones, so on and so forth. You can also choose and fine-tune the correct skin texture while you’re here. This stage is not unlike the character creators in RPGs or even in NBA 2K.

Step 3, hair. Hair is an important visual aspect for any character so it’s important to get this right as well. After you’ve modeled your digidouble’s head, you can next choose the closest hair preset for your character and customize from there. When I say hair, this includes hair on the head as well as eyebrows, eyelashes, and facial hair. This is the easy way. The harder way involves manipulating vertex groups along with hair properties. This is more complicated but yields more accurate results.

Step 4, fine-tuning. By this point, it’s not expected that you already have an accurate digidouble. You have a human, sure, but it most likely still looks like somebody else (or nobody). So the next step involves rounds and rounds of adjustments to be able to sculpt in the finer details of the face. This is where you need to pay close attention to facial proportions, eye shape, how the lips bulge, etc. Take your time dialing in the details; more time spent here leads to better results. Our eyes have evolved to recognize faces and as such are attuned to detect the smallest differences in people’s faces. So if you want to give your digidouble the best chance to pass for the real thing, you’d want to get even the tiniest detail right.

Step 5, clothing. Again, most human-generating 3D software have a ton of presets you can choose from so just pick the most apt clothing for your digidouble here.

Step 6, rigging. Now, it’s time to make your digidouble move. We won’t go into full detail here but what’s important to understand here is that this is where you map your digidouble’s face and body joints onto points that let you manipulate the digidouble for various facial or body movements. This step is really a hundred steps, just like each of the steps outlined previously. Perhaps I’ll be writing an article about rigging next, so stay tuned.

As with anything 3D, digidoubles need to be rendered just like any other 3D element in your scene. This is where render farms come in. Digidoubles are 3D objects composed of polygons and textures and materials that interact with light and as such also would require serious computational power to be converted for proper display on 2D screens along with the other 3D elements in the scene that these digidoubles find themselves in. And since Hollywood-level productions are always pushing the limits of how realistic digidoubles can get, the demand for rendering power gets pushed as well.

The earliest digidoubles for film were rendered on computers running on – wait for it – 2MB of memory (if you think about it, these machines are the grandfathers of the rendering machines in render farms!). While this sounds laughable now, back then in the 80s, this was cutting edge. So the more filmmakers and animators want to improve the realism and accuracy of digidoubles, the more the hardware requirement for rendering them gets.

We are in the golden era of visual effects and digidoubles are a huge part of it. For better or worse, I can only predict the continued increase in their usage in films and shows. While this perhaps puts a premium on, or at the very least lends a kind of prestige to movies like Top Gun: Maverick that prides itself in using zero CGI, the fact that digidoubles in particular and CGI in general are marching inexorably on towards more and more realism kind of renders the issue moot. I mean, if you can’t tell anymore whether what you are looking at is CGI or not, will it matter?

Digidoubles are here to stay.